16.02.2016, The Visitor

From Outsider to Diet Pioneer

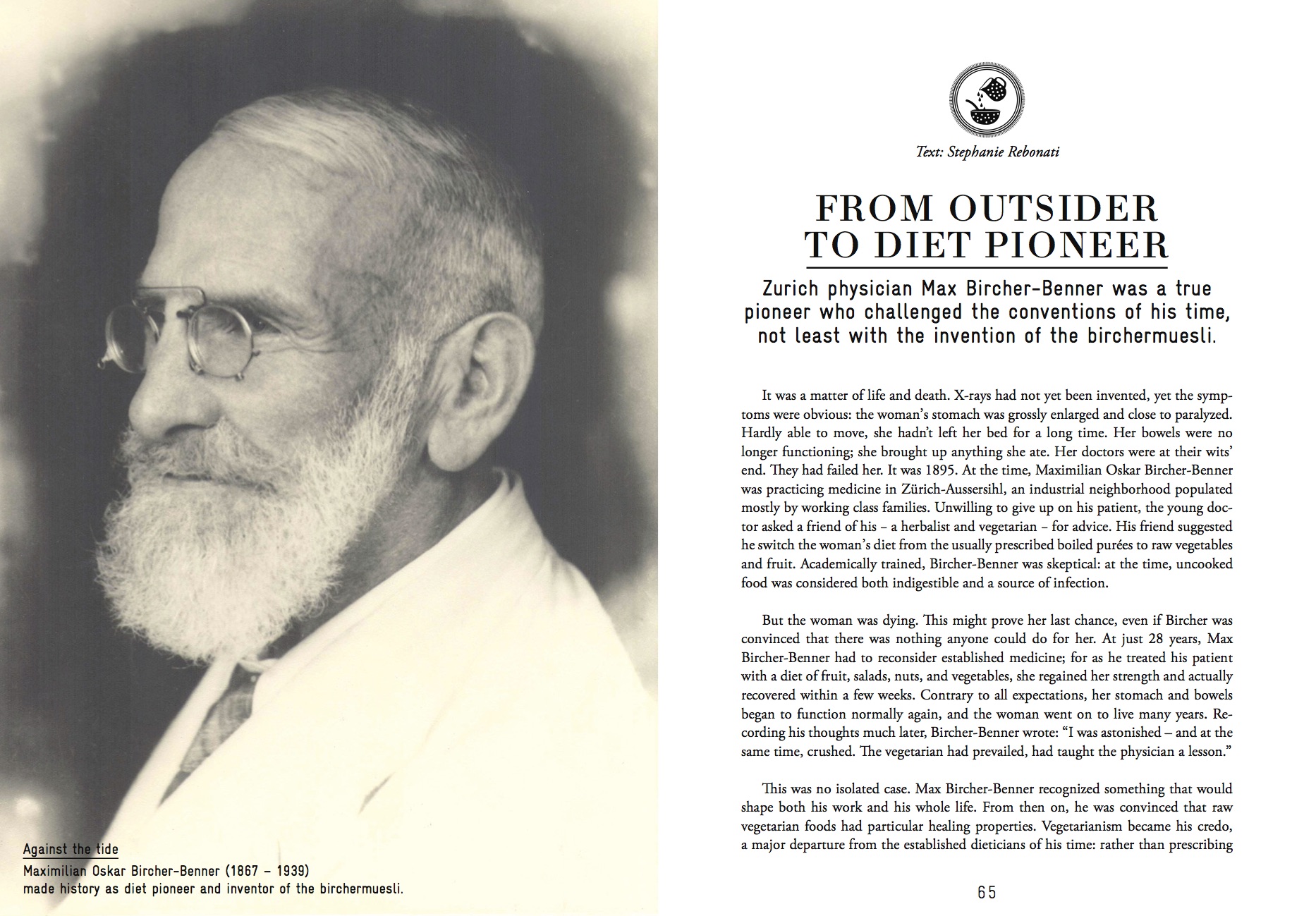

Zurich physician Max Bircher-Benner was a true pioneer who challenged the conventions of his time, not least with the invention of the birchermuesli.

Text: Stephanie Rebonati

Translation: Claudia Walder

It was a matter of life and death. X-rays had not yet been invented, yet the symptoms were obvious: the woman’s stomach was grossly enlarged and close to paralyzed. Hardly able to move, she hadn’t left her bed for a long time. Her bowels were no longer functioning; she brought up anything she ate. Her doctors were at their wits’ end. They had failed her. It was 1895. At the time, Maximilian Oskar Bircher-Benner was practicing medicine in Zürich-Aussersihl, an industrial neighborhood populated mostly by working class families. Unwilling to give up on his patient, the young doctor asked a friend of his − a herbalist and vegetarian − for advice. His friend suggested he switch the woman’s diet from the usually prescribed boiled purées to raw vegetables and fruit. Academically trained, Bircher-Benner was skeptical: at the time, uncooked food was considered both indigestible and a source of infection.

But the woman was dying. This might prove her last chance, even if Bircher was convinced that there was nothing anyone could do for her. At just 28 years, Max Bircher-Benner had to reconsider established medicine; for as he treated his patient with a diet of fruit, salads, nuts, and vegetables, she regained her strength and actually recovered within a few weeks. Contrary to all expectations, her stomach and bowels began to function normally again, and the woman went on to live many years. Recording his thoughts much later, Bircher-Benner wrote: “I was astonished – and at the same time, crushed. The vegetarian had prevailed, had taught the physician a lesson.”

This was no isolated case. Max Bircher-Benner recognized something that would shape both his work and his whole life. From then on, he was convinced that raw vegetarian foods had particular healing properties. Vegetarianism became his credo, a major departure from the established dieticians of his time: rather than prescribing tuberculosis sufferers a diet of milk, eggs, and meat, he was asking them to eat uncooked foods. It was five years later that he proudly presented his insights to Zurich’s Medical Society, and not without high expectations. Yet, what followed for him was tragic rather than triumphant. The Society laughed at his ideas and excluded him. Like after an excommunication, Max Bircher-Benner became an outsider – in hindsight, this turn of events would seem hardly comprehensible.

Bircher-Benner's Famous Invention

Today, Bircher-Benner’s invention is known the world over. Ubiquitous in supermarkets, in the kitchen cupboards of all levels of society, as part of the breakfast buffets in hotels, cafés, bakeries, restaurants, and canteens, muesli is a staple of our everyday diet. Creamy and sweet, the typical birchermuesli is a mixture of soaked oats, grated apple and juicy pears, nuts, honey, yogurt, milk, dried fruit and seeds – or a choice thereof. There are countless ways to prepare it.

Besides milk chocolate and cheese fondue, the birchermuesli is one of only a few Swiss foods that are popular all over the world. Though it may seem trivial, it is perhaps one of the most important contributions of our small country to a post-modern lifestyle. And through it, “Müesli” has become one of the very few Swiss words to enter the canon of truly international terms understood everywhere. We might even say that the muesli was Max Bircher-Benner’s contribution to a better world.

To understand his avant-garde thinking, we must remember that meat was king in his era. No meal was really complete without snouts, paws, or cured meats. Vegetables were seen as worthless side dishes, and sneered at by the public and medical profession alike. Max Bircher-Benner, however, examined the interplay of food, the human body, and society in depth. He considered an over-indulgence in food a metaphor for disease and societal decay. Looking back at his work today, his efforts might be considered either as a spur to health consciousness or a health craze. Either way, he is regarded as a pioneer of a way of thought that examines connections and establishes links. As a diet reformer, he made history, despite being ostracized by his contemporaries.

Success on the Zürichberg Mountain

This turn of events was sad, but perhaps hardly surprising, for Maximilian Oskar Bircher-Benner was already something of an outsider at birth. Born on August 22, 1867, he was a premature baby, scrawny and weak, and was overshadowed by his older brother until his adolescence. When his father, a farmer’s son who had worked his way up to become a notary, acted as guarantor for bankrupt friends, the family lost everything practically overnight, and was quickly excluded by bourgeois society. The father took to the bottle, and a storm broke over what had been a peaceful family life.

These experiences may well be at the root of Max Bircher-Benner’s attempt to reestablish “order.” In 1904, he opened a private clinic of five stories and sixty beds on the Zürichberg mountain, not far from the elegant Dolder Grand Hotel. With its large windows, bays, and balconies with prominent sunblinds, the spacious new building seems like a small castle today. In its day, the new clinic was called “Lebendige Kraft” – living strength – and it offered guests a treatment known as “ordinal therapy.”

The sanatorium’s leaflet advertised it as a “fighting institution” against the “deterioration of the constitution of human culture.” Renowned German writers Thomas Mann and Hermann Hesse, musicians such as violinist Yehudi Menuhin, the conductor Hans Rosbaud, statesmen and society women: all were guests here. The clinic became a mecca for the nature-oriented, its reputation comparable to those of the utopian colony Monte Verità in Ascona, or the alpine clinics in Davos and Leysin.

Life at the Bircher-Benner clinic was subject to a strict regimen. The guests rose at daybreak. Regular strolls through the close-by forest were part of the daily program, as were garden work, gymnastics, and croquet. Cold baths and massages were integral to treatment – as was Max Bircher-Benner’s apple diet dish, today’s muesli, which was seen as cure for digestive problems and migraines. In 1909, Thomas Mann described his stay on Zürichberg as follows: “My stubborn digestion improved remarkably, as it had never before. And the stay was rendered agreeable by friendly company and the beautiful location of the institution. The light on certain evenings will remain etched on my memory.”

A Holistic Way of Thinking

Though ostracized from Zurich’s medical circles, Max Bircher-Benner gained an international reputation among herbalists. His writings were published in Berlin and St.Petersburg, and he lived in one of Zurich’s upper class neighborhoods with his family of seven. Renouncing meat and alcohol, he never separated his professional from his private life. His sister was the chief housekeeper at the sanatorium; his sons later worked as physicians; and his daughters taught dance gymnastics and ran the in-house book-binding atelier. The underlying belief was that to live in harmony with nature, and to practice moderation in all things, was the cornerstone to a long life. Business boomed and Max Bircher-Benner emerged one of Switzerland’s most famous citizens.

With his success, he had restored the “order” he perceived as shattered by his father’s bankruptcy. On Saturdays, it was a family tradition to attend the “Thé dansant” at the Dolder Grand Hotel. He encouraged his daughters to wear lipstick, dress fashionably, wear smart hats and geometrically-cut skirts with stylish, low waistlines. But one thing the husband and father did not condone: women in trousers.

Max Bircher-Benner not only invented the muesli, he shaped the image of a new, holistically thinking physician. His focus turned to internal medicine early on; a diagnosis was always focused on finding the underlying causes of an illness, and his prescribed treatment was an attempt to address them. As such, he was the first proponent of a holistic form of medicine. His totem was a green leaf; dietetics, his life. Commenting on his own practice, he wrote: “It is much quicker to write a prescription than to explain to a patient his own disorder, to instruct him on dietetics and a disciplined lifestyle, and to win him over for its implementation.”

In 1939, Max Bircher-Benner died of a heart attack at 72 years old. His clinic “Lebendige Kraft” was later renamed in his honor. The “Bircher-Benner Clinic” remained in the family until 1978. In 1994, the Canton of Zurich sold the property to the Zurich Insurance Group, which currently uses it as an education center and seminar hotel. Whether Bircher-Benner’s ghost still wanders its halls to inspire visitors may be questionable. What is certain is that the wholesome delicacy he invented, the muesli, is still highly popular. Continually reinterpreted and reinvented, it has made its way from the Zürichberg into the big, wide world.